|

These were the children of the Moriscos who had been expelled from Valencian territory two years earlier in the biggest expulsion that Spanish kingdoms had ever seen. To put this into historical context, we need to go back a few centuries. When Christian troops "reconquered" much of Xarq al-Andalus - what would later become the Kingdom of Valencia from the second half of the 13th century onwards - many Muslim inhabitants left, but a large number stayed, although they were increasingly marginalised and sometimes persecuted under Christian rule. Whole villages of Muslims remained especially in the mountainous regions of Valencia and those who remained, known as Mudejars (from Arabic mudajjan, “permitted to remain”) were initially allowed to practise their religion, albeit with restrictions.

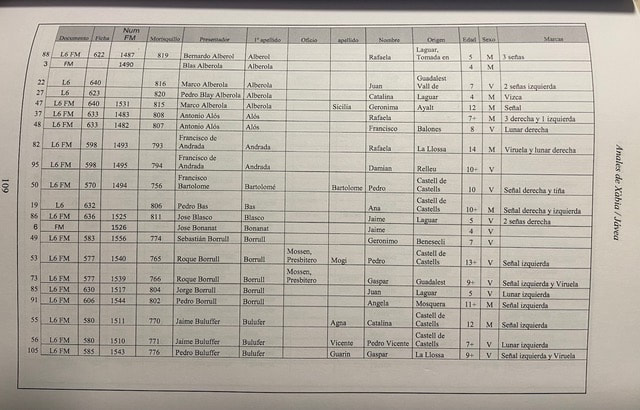

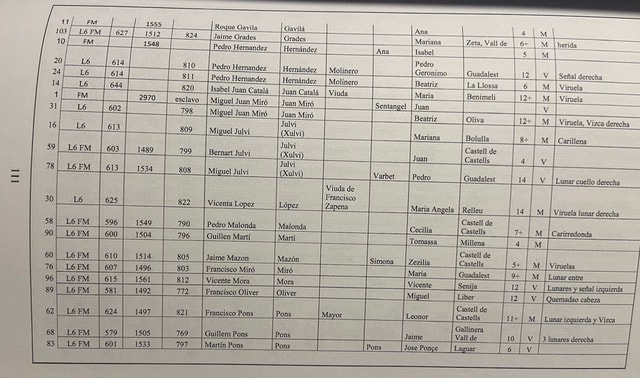

By the mid 15th century, however, there were clear signs of increasing political, religious and cultural intolerance. And with the Christian conquest of the kingdom of Granada (1492), the last Muslim stronghold, conditions for the Muslims changed dramatically. In a series of royal decrees in the early 16th century, the Mudejars were given the choice of converting to Christianity or leaving the country. It wasn´t until 20 years later that a popular uprising of the Germania de València led to the forced conversion of thousands more Muslims (Royal Decree of 4 April 1525). Although nominally Christian, the majority of these Moriscos, as they were known, clung to their ancestral Islamic faith, which they continued to practise secretly in the privacy of their homes. (The Oran Fatwa of 1504 - an Islamic legal ruling - allowed the Muslims of the Iberic peninsula to outwardly conform to Christianity if necessary for survival, without committing apostasy or treason ). It was an open secret and the monarch and the Church knew that the majority were not really Christians and this fact disturbed them. Finally in a decree of 22 September 1609 King Felipe III justified his decision to expel the Moriscos of the Regne de Valencia, by stating that the efforts to truly convert them had been in vain. Between 1609 and 1614 around 300,000 Moriscos were expelled from the Kingdom of Valencia. This was a great tragedy for a people who knew no other country as their home, for the Morisco population of the Kingdom of Valencia were for the most part the heirs of the ancient settlers who had lived in these lands since the end of prehistoric times ! After the expulsion, a great many morisquillos (children of the expulsed) between the age of 4-12 were found in the kingdom.There is no consensus on exactly how many, but the latest studies (Gironés) seem to put the figure at 2,447 children. However, there could easily have been more. After the expulsion of their parents in 1609, the state did not care for these children. Some of them were taken in by the Church, but most of them were taken in by rich families to be servants or slaves. Some were even sold by soldiers to people from other kingdoms in Spain and others were sold to Italian merchants. It was not until 1611 that King Felipe III decided to carry out a census to trace these children. In his decree of 29 August, he stated that the children should be brought up in Christian families in the true faith and that they should not be treated as slaves. But in reality, there was no mechanism in place to control this. In Xàbia the census was held on 25 September. All the residents who had a morisquillo in their home were asked to come and present him/her to the authorities. Officially there were 94. They may well have been more. Infant mortality was high in those days. And it is possible that not all children were presented, as it was decreed that a household could not have more than two Morisco children. The census recorded the name, age, place of birth and special characteristics of a child. The forenames were the traditional local names they had received at baptism, or the names given to them by the family they lived with. The surname was that of the Valencian family. Most of the children came from the mountains of Valencia such as Vall de Laguar, Guadalest, Castell de Castells, Alcalà and many other places. Their ages range from as young as 4 years old (meaning they were 2 years old when they lost their parents !) to 14 years old. At the beginning of the 17th century there were 450 houses in Xàbia, which would mean 450 families…more or less. Theoretically there could have been a Morisquillo in every 5th household ! One wonders : what became of these children ? How many remained in Xàbia ? Those who stayed must have become fully integrated over time. And how many people in Xàbia today have a forgotten Morisco ancestor they have no clue about…….?!

0 Comments

It´s not really a sport, but rather a hobby (afición)„ says Pascual Mayans Zaragozi, secretary of the club Colons Esportius de Xàbia. In fact, we are referring to the club of pigeon fanciers or „colombaires“ as they are called, whose members dedicate themselves to the breeding and care of these birds……(and the sport is practised by the birds !) Pigeon-breeding (colombicultura) has been known for centuries, but it was only at the beginning of the 20th century that it became an official sport with its own set of rules, although the first society for pigeon-breeding for pleasure ("por la diversión") was founded in Murcia in 1773. Pigeons have undoubtedly always existed in the Iberian Peninsula, but it was the Arabs who brought the domesticated pigeon to Spain in the 8th century. These were bred for their size and their main use was as food. Initially only the rich could afford to keep them (for food and pleasure), but over the centuries most people had them. As well as providing food, their droppings were good for fertilising the land. They were also used as messengers, especially by monks, to communicate between monasteries. So it was often the monks who bred them. One of these monks, Fraile Llaudì, crossed the large pigeon with the slighter messenger pigeon, thus creating the ancestor of the one used today for this sport. The most prized pigeon today is the "buchon Valenciano". And it certainly is a very Valencian sport. In this sport, the male pigeon (palomo) has to woo or conquer the female (paloma) through innate or trained qualities. These are related to the size, intelligence and cunning of the palomo, virtues that help him to pursue, attract and conquer the paloma. A breeder's aim is to breed males with great physical appearance and seducing demeanor in order to best attract a female. After a gestation period of 20 days, a paloma always lays only 2 eggs. When the chicks (pichones) are 30 days old, they are separated from their mother and kept together in a pen until their behaviour tells the trained eye of the breeder which are males and which are females, between 3 and 6 months. When they are separated, the females are kept together in one pen, while the males are kept in separate pens. When the males reach the age at which they start to be attracted to the opposite sex- between 6 and 12 months- and after their first moult, their wings are painted in bright colours, with each breeder having his own distinct colour combinations to distinguish them as his own.The colombaire then chooses for the male a paloma of the same age, whose tail feathers are slightly clipped and one or two artificial white feathers are attached to the tail. This will be the distinguishing mark by which the palomo will later recognise its mate. They are then left together in a pigeon coop for 7-8 days to "fall in love". After this time they are separated. For the next few days they are sad and unhappy. After a few days, the paloma is introduced to 4-5 other palomos in the same way. When this process is over, a trial is carried out. About 2 hours before sunset, all the males that were introduced to her are let out of their cages and when the female is released, all the males want to be with her and seduce her. This is when the courtship rituals begin. When she tires of them, she flees with all her suitors behind her, looking for a place to hide from them, which she might find in the dense foliage of a tree, a hollow trunk or a hole in a wall. This could be up to 6 km from her home. As fatigue and hunger override lust, pigeons will begin to retire from the chase and return to their coop, and only the most hardy and most ambitious one who does find her will seduce her and fly back with her before it gets dark. Competitions are basically just that. The palomo with the best instincts for seduction and perseverance, and who spends the most time around her, gets the prize. The winner is not the most athletic, or the toughest, or the most pure-bred, but the one who is the most polite, the one who shows the most constancy, and the one who has the strongest reproductive instinct. Interestingly,the palomos each have their own tricks and techniques for dealing with their opponents, and the better ones even watch how the others react and adapt their game accordingly. There are usually at least 75 palomos competing for the attention of a single paloma. A competition lasts for 6 consecutive days, each day for 2 hours. Two judges award points for the time spent in the air with the female and for the time spent on the ground performing courtship rituals. Extra points can be awarded for the elegance of the flight and the courtesy with which he treats the female. With so many palomos around the paloma, it's amazing what a phenomenal memory and sharp eyesight a judge must have to keep track of the action ! From the ground, the owners follow the flight of their pigeons - easily identifiable by their colours. The competitions are organised by the Federación Española de Colombicultura Valenciana, a body created in 1944 to recognise pigeon-breeding as a national sport. First of all, there are the local and comarca competitions. Then there are the provincial, national and even international levels. This sport, which is said to have originated in the province of Valencia, has also become popular in Catalonia and Andalusia and, to a lesser extent, in other parts of Spain. It is even practised in several South American countries and some other European countries, such as Portugal and Austria. The Xàbia Pigeon Club was founded around 1940, just after the Civil War. Its members kept their pigeons at home, but met at the Bar Imperial, behind the Ayuntamiento. Towards the end of the 1960s, a widow who owned a house opposite the bar La Rebotica bequeathed it to the Ayuntamiento of Xàbia on her death, with the right of usufruct granted to the pigeon club La Javiense, as it was known at the time. This was the centre of the club for the next 25 years or so. In the 1990s, when people began to feel disturbed by the pigeons in the pueblo, the Ayuntamiento gave them permission to create a club on the outskirts of the old town, just south of the Rio Gorgos Barranco. Here they have pigeon coops (cajones) for all the members' birds. They also have a clubhouse where meetings and social events are held. Xàbia´s club Coloms Esportius is proud of the high quality of its pigeons. In the last 60 years, many have taken part in the national championship, three of them in the last 10 years. In the 80's the club had over 200 members. In 1983 Xàbia even hosted the national championship cup, the Copa Su Magestat Rey Juan Carlos I. However, the number of members has gradually declined over the last 10-15 years.Today the club has no more than 36 members. In an attempt to change this, the club periodically visits schools in Xàbia to make young people aware of this ancient and surprising activity, so that the new generations may take an interest in it and ensure that this unique Valencian sport does not disappear. There are so many extra-curricular activities available for young people today that there is little or no interest in this age-old pastime. Although there are still more than 9000 pigeon fanciers in the Comunidad Valenciana, one gets the impression that in Xàbia pigeon-breeding may soon be a thing of the past. There are many positive aspects to pigeon breeding : among others, the close relationship that develops between the fancier and his pigeons, the emotion that comes from observing the behaviour of these birds, the contact with nature, the brotherhood between members. Who knows, perhaps one day, this sport will take flight again in Xàbia. * The information in this article has kindly been provided by Pascual Mayans Zaragozi, secretary of the club Colons Esportius de Xàbia. In the Middle Ages, this area attracted many hermits who were inspired by it for meditation and devotion to God.

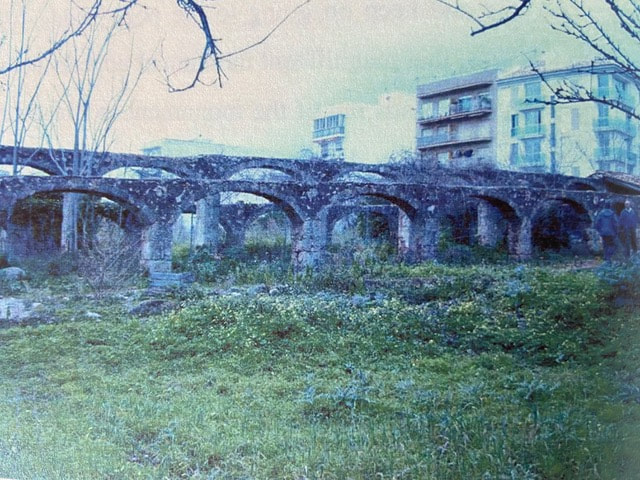

Towards mid 14th century the ascetic and erudite St. Jerome became very popular. St. Jerome (b. ca. 347 in Dalmatia, d. ca. 419 in Bethlehem) , who was a scholar and translator of the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin, lived for several years as a hermit and was founder of a Hieronymite monastery and convent in Bethlehem. Inspired by St. Jerome, many Hieronymites came as hermits to the seclusion of the Plana and lived in the many caves on the lower part of the Cabo San Antonio. They became well-known for their piety and self-abnegation and many would come from far and wide to pay them their respects. These caves are still called Coves Santes (holy caves), as they have been called for centuries because of these hermits. The hermits would come together from time to time to discuss fundaments of their belief and in 1374 they decided to ask the Pope for permission to found a monastery on the Plana. Three of the hermits then journeyed to Avignon, seat of Pope Gregory XI and returned with a papal bull, granting them their wish. The same year, construction of a small, very elementary monastery began. It was finished in only eleven months. It was mainly financed by their patron, the royal Duke Alfonso of Aragon, Alfons el Vell, Duke of Gandia, Marquis of Denia and grandson of King Jaime II. In 1375 the twelve hermits moved from their caves to the monastery, with Friar Jaime Ibañez as their prior. It was the first Hieronymite monastery in Spain. Here they lived in silence, praying and meditating. They lived in utter poverty, sometimes working in the fields for subsistence, sometimes begging, which the Pope had permitted them to do. In those days, Xabea, as it was called, was often plagued by Berber pirate attacks. In 1386 even this poverty-stricken monastery was not spared. A band of pirates entered and brutally harassed the monks, taking nine of them as hostages, one of whom died on the way down to the port. They were taken to Algiers and Bugia, today in Algeria. The Duke paid a huge ransom to set them free and they were returned to Xabea in 1392. After the attack they never felt safe again here. Duke Alfonso also feared for their safety, so in 1388 he bought the territories of Cotalba, 8 kms inland from Gandia from the Muslim owner, and donated them for the construction of a new, larger monastery. In that very year the construction works began, planned and overseen by the Duke´s own mayordomo (chief administrator) Pere March, father of the famous poet Ausias March (later, several members of the March family would be buried in a chapel of the church). In the following year, the monks moved into the Monastery of St. Jerome of Cotalba. This beautiful albeit simple monastery is today one of the most historic monastic constructions in the Comunidad Valenciana. It is no longer a monastery (since 1835), but has been conserved in the original state for tourist visits. The original Monastery of St. Jerome of the Plana remained abandoned for several centuries until towards end of the 17th century, when, legend has it, a hunter found a canvas in a tree on the monastery grounds representing the Virgin Mary surrounded by angels, with Jesus on her lap and St. Jerome nearby. This „miracle“ finding prompted the reopening of the monastery and the veneration of the Virgin of the Angels. The monastery, despite renovations and remodelling works after pillages and wars, maintained its original 14th century features until 1962 when unfortunately a massive refurbishment was undertaken, and most of the original features were destroyed. In 1994 certain elements were salvaged and returned to their original state. Today it is called the Sanctuari de la Mare de Déu dels Àngels (Hermitage of Our Lady of the Angels) and is run by nuns, Daughters of St. Mary of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Every year the fiesta of the Plana (usually from 1st-3rd August) commemorates the re-founding of the hermitage in a procession with the residents of the Plana, where the original 17th century painting is carried around the grounds of the hermitage and a Mass is held. The canvas then returns to the church of the hermitage as its central alter piece. In the courtyard of the hermitage there is also a series of ceramic tile paintings depicting varoius episodes of the founding of the original monastery. There is access to this part of the hermitage on most days. The Hermitage is not open for tourist visits but anyone can join Mass held daily at 9am in the church where the canvas painting is housed. On Sundays and holidays mass is held at 10am and again at 19.00. Often taken as another name for Cap Prim, it is in fact the whole promontory from Cap Prim in the North, to Cap de la Nao further East, and Ambolo in the South ( see map below ) and consists not only of the coast but the inland too. There is a legend, which has no archaeological basis - so far !!!! - that there was a famous St. Martin´s monastery there in the 6th century, which gave its name to the Cape. San Gregorio de Tours, a cleric and historian living in the 6th century wrote in his De Gloria Confessum that this monastery was attacked and ransacked by soldiers of the Visigoth King Leovigildo (568-586 a.d). All the monks had already fled to a nearby island, and only the old abbot remained. When a soldier raised his sword to smite the abbot, he suddenly fell to the ground and died. On hearing this, the king ordered his men to return all the booty they had taken from the monastery. While there must be some truth in this event, it is questionable whether it took place here in Xabià. Gregorio de Tours wrote that the monastery was "between Sagunto and Cartago Spartaria" (Cartagena). It could have been anywhere ! No remains have been found on Cap Martì. But on the other hand, Roc Chabàs (1845-1912) also cleric and historian, wrote about a document he had seen of a 1556 notarial sale of a piece of land in Cap Martì that was next to the ruins of a monastery. Unfortunately, he did not submit the actual document.

The belief that this monastery existed in Xabià persists and some believe it had been where many centuries later the Augustine Convent was built in the Pueblo ( today the covered market, Mercado de Abastos ). Others believe it to have been on the Cap Sant Antoni where many chapels, ermitas and monasteries have been built over the centuries. However, as long as there is no archaeological proof, this St. Martin`s monastery remains in the realm of legends. Cap Martì was originally the name of today´s Cap de la Nao. That we know as a fact. A conjecture is that the name was given by Venetian mariners who, from the sea, saw the prominent headland as a "capomartino", the commanding post or captain´s bridge of a galley. So Venetian cartographers, who were the great marine cartographers of the Middle Ages, called it Capo Martino in all their maps. Centuries later, towards the end of the 18th century, and maybe due to some confusion, it became Capo San Martino. This could have been because of the existence of a defence post called Castillo San Martì not so far away, marked probably on the map as C° San Martino (C° being an abbreviation either of "castillo" or of "cabo"). This same error, made by a certain Tofiño (1732-1795), was most probably also the reason why he saw the whole promontory as the cape, and not just the one headland, thus changing the latter´s name which was then called Cap de la Nao (nao = ship) for its shape. Nowhere do we have documents that really depict the history of Cap de Martì. Assumptions are made, theories are developed, but in the end, each one has to decide what he/she wants to believe. It is interesting to see how fact and fiction intertwine over the centuries and probably we shall never find out what really happened. Today Cap Martì is so strewn with tourist houses, that modern archaeological methods cannot be used to study the terrain. Cap Martì will surely continue to guard its mystery for a long time. Although Xàbia remained in the rear throughout the war (1936-39), the importance of the defense

and control of the stretch of coast between Dénia and Xàbia, made the government of the Republic create a coastal defensive line between the Marines and Portitxol with the installation of various defensive constructions whose purpose was to stop possible attacks by the Francoist army and protect coastal shipping in the area. The most important defensive structure built in Xàbia was the great battery of Portitxol. Built about 90 meters above sea level, this robust and extensive semi- subterranean battery, built with thick cement concrete walls, protected the wide bay of Xàbia, to the northwest, and the small bay of Portitxol, to the south-east. On Saturday, June 17, we will be able to visit, thanks to the kindness of the owner of the plot where it is located, Pasqual Pastor Cardona, the preserved remains of this construction. The route will start at 10:30 a.m. in the Caleta car park, we will walk to the Portitxol viewpoint, visit the remains of the battery and return to La Caleta. Here's a brief summary of the activities planned for the next couple of months:

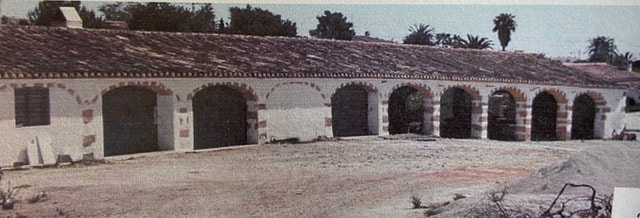

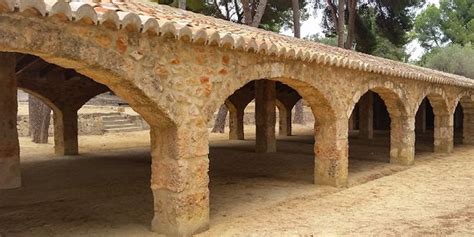

May 17, Wednesday, at 7:00 p.m. A talk about the amphorae discovered underwater in the Xàbia area. May 26, Friday, at 18:30, An guided walk from the Roman ruins near the Parador, to the Séquia de la Noria, through the Saladar. June 17, Saturday (time to be determined), a visit to the Portixol Civil war battery. These rural architectural structures - unique to the Comunidad Valenciana - appeared at the end of the 18th century, with the onset of the raisin trade, which brought work and much wealth to the Valencian region, especially the Marina Alta. The process of scalding the grapes before putting them out to dry, made their skin crack, thus speeding up the drying process.This, however, made them very vulnerable to mould, caused by rain, night humidity and morning dew. Therefore the grapes had to be removed to a shelter on rainy days and at night. This was the purpose of the riuraus.

But where could the word „riurau“ have come from? It is not Valenciano, nor is it Spanish. There are several theories, most of which can be disregarded. One such theory is that it came from the Arab language: „raf“, meaning roof or shelter. Duplicating the word, as is sometimes done in Valenciano, produces raf-raf, which could have been distorted to riu-rau. However, this is very unlikely since riuraus only appeared some 200 years after the expulsion of the moors. Another even more unlikely theory is that it came from the English „ raisin house“, distorted to riu rau. However, this seems rather fanciful since in the 19th century when these constructions appeared, there were virtually no British people living in the region who could have coined the phrase ! A third theory is that it could have something to do with „riu“, river, as of „drainage“ of the roof……..well, one wonders how seriously one can take that ! The most plausible version, one that Luis Fornès elaborates in his book „Valencian Riuraus“, is that it comes from the Occitan language, more precisely, from an Occitan dialect: Provençal. Since the 16th century, there was considerable emigration from Southern France, mainly from the Provence, where Provençal was spoken, a dialect that has much resemblance to Catalan, Valenciano and Mallorquin. This fact facilitated emigration to and integration into the Kingdom of Valencia. It is therefore not too far-fetched to surmise that there could have been some influence on the language. A riurau was almost always either on its own in a rural area, or was attached to a rural house - casa de campo. The theory is that these rural buildings could originally have been called „ostal rural „ ( rural house ), which in the Provençal dialect would be „ ostau rürau„ since the -al endings become -au in Provençal. With time, the noun „ostau“ must have been dropped, and the shelter was just called „ rürau“. Since the „ü“ , which is generally described as being somewhere between an „i“ and a „u“ , does not exist in Valenciano, it could have been pronounced as „ iu “ by the locals. So it would seem that the name came from its rural status : „rural“ > „rürau“ > „riurau“. Of course, so far there have been no conclusive studies on the etymology of the word riurau, so it is still open to debate. This latter seems to be the most probable explanation until a new theory appears. Source : „ Valencian Riuraus „ by Lluis Fornés To understand why this is so, one has to go back to the origins of the legend of the Santa Casa (the Holy House), the dwelling in Nazareth (Israel) where the Virgin Mary was born, where the Annunciation occurred, where Jesus lived until his 30th year, and where Joseph died. In the year 1291, when the Moslems definitively expelled the Crusader Knights from Palestine, legend has it that this house was miraculously transported by angels through the skies, first to Tersatto in Dalmatia (Croatia). Then a few years later in 1294, after a few other stops, it was put down by the angels in its final resting place, a laurel grove, (in Latin : lauretanum), from which Loreto is named, near Ancona, Italy. (Another story for the name was that the angels put the house down on the land of a noblewoman named Loreta). Here it stands to this day within the Basilica of the Holy House, one of the most visited Marian shrines in the world. A version which may be more plausible for us today, is that the wealthy Italian Angeli family had the Holy Family´s house disassembled to save it in the face of the Moslem invasion of 1291. They had it shipped to Italy via modern-day Croatia. The efforts of the Angelis turned into the legend that the angels had scooped up the holy abode. Science has proven that the house is in fact built with bricks that date back to the time of Christ and are of the same substance as other houses in Nazareth at that time. The „flight“ of the house and its long conservation explains why in 1920 the Virgin of Loreto was officially decreed the patroness of aeronautics and builders. So how come she became the patron saint of the fishermen of Xàbia ? Here too there is more than one legend. One popular story goes like this : in 1850 an Italian ship went aground off the coast of Cap Prim. Some fishermen went in their boats to save whom they could, but found only an icon of the Mare de Deu de Loreto to save. Another version is based on a document written in the 18th century. In March 1679 a skirmish between a Genovese ship called the „Virgen de Loreto“ and an armada of seven Turkish ships was seen by local fishermen off the coast of Xàbia. Miraculously, the Italian ship won the combat. This prompted the fisherman to pronounce the Virgin of Loreto as their patron saint. But in actual fact, we do not know when or why the fishermen of Xàbia chose the Virgen de Loreto as their patron saint. What we do know is that there was a chapel already dedicated to her in 1515 near the Puerta del Mar in the eastern part of the town, an area mainly inhabited by fishermen. However, we do not know whether she was revered by the inhabitants of Xàbia generally or whether the fishermen had already chosen her as their patron saint. A document of 1847 describes the chapel as rectangular with a large portico with 3 Mudejar-style naves, supported by 8 columns. The local school was also held here and there was an annex for the teacher´s quarters which was most probably added in 1556. We also know that in the 18th century some fishermen, who had died in a misfortune on the sea, were buried in this chapel. The chapel seems to have been renovated towards the end of the 18th century. Almost a century later it had again become so dilapidated that it was demolished after a major accident, where a part of the nave fell, killing one man. Today there is a public garden where the chapel stood. The only element that remainds us of the chapel is the „Jardinet de Loreto“, an edifice with a neo-Gothic style stone cross (1954), and the fountain decorated with a representation of the Holy Family´s House and a figure of the Virgin of Loreto carrying her son Jesus, built in 1923. This square is next to the Restaurant Trinquet and is called Plaza Vicent de Gràcia, in honour of the sandstone craftsman who made it. Since 1896 the fishermen´s annual fiestas in the Port are held in honour of their patron saint, Mare de Deu or Virgen de Loreto . These begin towards the end of August and end always on the 8th of September, the birthday of the Virgin Mary. (The official day of the Virgin of Loreto is celebrated in most countries on the 10th of December, the day when the Santa Casa arrived in Loreto) The fishermen´s new church, built in the mid 60s, is also dedicated to the Virgin of Loreto, but that is material for another article ………. On Wednesday, February 1st, there will be a talk on the Portixol excavations at 7:00 p.m. in the museum's conference room. The presentation will be made by archaeologists responsible for the project.

Here is some earlier publicity: Oct 22nd 2022 Municipal Museum and University of Alicante to begin archaeological digs on Portitxol island - The latest excavations will be carried out during October and November and will consist of intensive archaeological trials across the entire surface of the island. www.javeamigos.com/municipal-museum-and-university-of-alicante-to-begin-archaeological-digs-on-portitxol-island/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=municipal-museum-and-university-of-alicante-to-begin-archaeological-digs-on-portitxol-island |

ACTIVITIES

Categories |

- Home

- Blogs

-

Projectes

- Premio de Investigación - Formularios de Inscripción

-

Traducciones Translations

>

-

DISPLAY PANELS - GROUND FLOOR

>

- THE STONE AGES - PALAEOLITHIC, EPIPALAEOLITHIC AND NEOLITHIC

- CAVE PAINTINGS (ARTE RUPESTRE)

- CHALCOLITHIC (Copper) & BRONZE AGES

- THE IBERIAN CULTURE (THE IRON AGE)

- THE IBERIAN TREASURE OF XÀBIA

- THE ROMAN SETTLEMENTS OF XÀBIA

- THE ROMAN SITE AT PUNTA DE L'ARENAL

- THE MUNTANYAR NECROPOLIS

- ARCHITECTURAL DECORATIONS OF THE PUNTA DE L'ARENAL

- THE ATZÚBIA SITE

- THE MINYANA SMITHY

- Translations archive

- Quaderns: Versión castellana >

- Quaderns: English versions >

-

DISPLAY PANELS - GROUND FLOOR

>

- Catálogo de castillos regionales >

- Exposició - Castells Andalusins >

- Exposición - Castillos Andalusíes >

- Exhibition - Islamic castles >

- Sylvia A. Schofield - Libros donados

- Mejorar la entrada/improve the entrance >

-

Historia y enlaces

-

Historía de Xàbia

>

- Els papers de l'arxiu, Xàbia / los papeles del archivo

- La Cova del Barranc del Migdia

- El Vell Cementeri de Xàbia

- El Torpedinament del Vapor Germanine

- El Saladar i les Salines

- La Telegrafía y la Casa de Cable

- Pescadores de Xàbia

- La Caseta de Biot

- Castell de la Granadella

- La Guerra Civil / the Spanish civil war >

- History of Xàbia (English articles) >

- Charlas y excursiones / talks and excursions >

- Investigacions del museu - Museum investigations

- Enllaços

- Enlaces

- Links

-

Historía de Xàbia

>

- Social media

- Visitas virtuales

- Tenda Tienda Shop

RSS Feed

RSS Feed