|

These were the children of the Moriscos who had been expelled from Valencian territory two years earlier in the biggest expulsion that Spanish kingdoms had ever seen. To put this into historical context, we need to go back a few centuries. When Christian troops "reconquered" much of Xarq al-Andalus - what would later become the Kingdom of Valencia from the second half of the 13th century onwards - many Muslim inhabitants left, but a large number stayed, although they were increasingly marginalised and sometimes persecuted under Christian rule. Whole villages of Muslims remained especially in the mountainous regions of Valencia and those who remained, known as Mudejars (from Arabic mudajjan, “permitted to remain”) were initially allowed to practise their religion, albeit with restrictions.

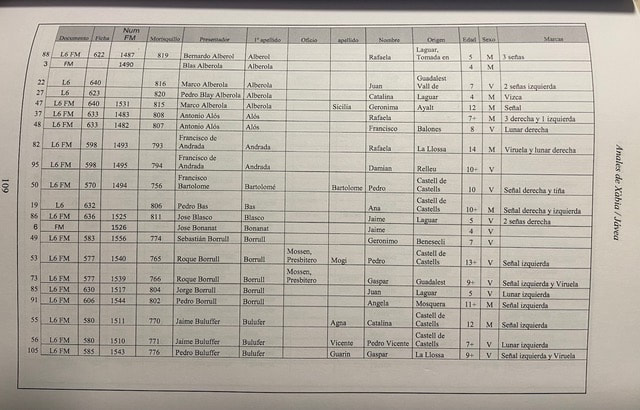

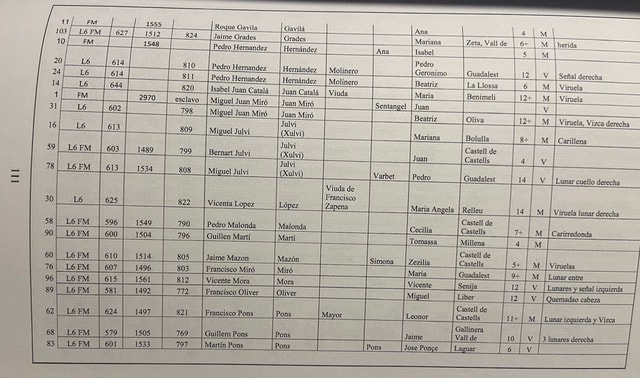

By the mid 15th century, however, there were clear signs of increasing political, religious and cultural intolerance. And with the Christian conquest of the kingdom of Granada (1492), the last Muslim stronghold, conditions for the Muslims changed dramatically. In a series of royal decrees in the early 16th century, the Mudejars were given the choice of converting to Christianity or leaving the country. It wasn´t until 20 years later that a popular uprising of the Germania de València led to the forced conversion of thousands more Muslims (Royal Decree of 4 April 1525). Although nominally Christian, the majority of these Moriscos, as they were known, clung to their ancestral Islamic faith, which they continued to practise secretly in the privacy of their homes. (The Oran Fatwa of 1504 - an Islamic legal ruling - allowed the Muslims of the Iberic peninsula to outwardly conform to Christianity if necessary for survival, without committing apostasy or treason ). It was an open secret and the monarch and the Church knew that the majority were not really Christians and this fact disturbed them. Finally in a decree of 22 September 1609 King Felipe III justified his decision to expel the Moriscos of the Regne de Valencia, by stating that the efforts to truly convert them had been in vain. Between 1609 and 1614 around 300,000 Moriscos were expelled from the Kingdom of Valencia. This was a great tragedy for a people who knew no other country as their home, for the Morisco population of the Kingdom of Valencia were for the most part the heirs of the ancient settlers who had lived in these lands since the end of prehistoric times ! After the expulsion, a great many morisquillos (children of the expulsed) between the age of 4-12 were found in the kingdom.There is no consensus on exactly how many, but the latest studies (Gironés) seem to put the figure at 2,447 children. However, there could easily have been more. After the expulsion of their parents in 1609, the state did not care for these children. Some of them were taken in by the Church, but most of them were taken in by rich families to be servants or slaves. Some were even sold by soldiers to people from other kingdoms in Spain and others were sold to Italian merchants. It was not until 1611 that King Felipe III decided to carry out a census to trace these children. In his decree of 29 August, he stated that the children should be brought up in Christian families in the true faith and that they should not be treated as slaves. But in reality, there was no mechanism in place to control this. In Xàbia the census was held on 25 September. All the residents who had a morisquillo in their home were asked to come and present him/her to the authorities. Officially there were 94. They may well have been more. Infant mortality was high in those days. And it is possible that not all children were presented, as it was decreed that a household could not have more than two Morisco children. The census recorded the name, age, place of birth and special characteristics of a child. The forenames were the traditional local names they had received at baptism, or the names given to them by the family they lived with. The surname was that of the Valencian family. Most of the children came from the mountains of Valencia such as Vall de Laguar, Guadalest, Castell de Castells, Alcalà and many other places. Their ages range from as young as 4 years old (meaning they were 2 years old when they lost their parents !) to 14 years old. At the beginning of the 17th century there were 450 houses in Xàbia, which would mean 450 families…more or less. Theoretically there could have been a Morisquillo in every 5th household ! One wonders : what became of these children ? How many remained in Xàbia ? Those who stayed must have become fully integrated over time. And how many people in Xàbia today have a forgotten Morisco ancestor they have no clue about…….?!

0 Comments

|

ACTIVITIES

Categories |

- Home

- Blogs

-

Projectes

- Premio de Investigación - Formularios de Inscripción

-

Traducciones Translations

>

-

DISPLAY PANELS - GROUND FLOOR

>

- THE STONE AGES - PALAEOLITHIC, EPIPALAEOLITHIC AND NEOLITHIC

- CAVE PAINTINGS (ARTE RUPESTRE)

- CHALCOLITHIC (Copper) & BRONZE AGES

- THE IBERIAN CULTURE (THE IRON AGE)

- THE IBERIAN TREASURE OF XÀBIA

- THE ROMAN SETTLEMENTS OF XÀBIA

- THE ROMAN SITE AT PUNTA DE L'ARENAL

- THE MUNTANYAR NECROPOLIS

- ARCHITECTURAL DECORATIONS OF THE PUNTA DE L'ARENAL

- THE ATZÚBIA SITE

- THE MINYANA SMITHY

- Translations archive

- Quaderns: Versión castellana >

- Quaderns: English versions >

-

DISPLAY PANELS - GROUND FLOOR

>

- Catálogo de castillos regionales >

- Exposició - Castells Andalusins >

- Exposición - Castillos Andalusíes >

- Exhibition - Islamic castles >

- Sylvia A. Schofield - Libros donados

- Mejorar la entrada/improve the entrance >

-

Historia y enlaces

-

Historía de Xàbia

>

- Els papers de l'arxiu, Xàbia / los papeles del archivo

- La Cova del Barranc del Migdia

- El Vell Cementeri de Xàbia

- El Torpedinament del Vapor Germanine

- El Saladar i les Salines

- La Telegrafía y la Casa de Cable

- Pescadores de Xàbia

- La Caseta de Biot

- Castell de la Granadella

- La Guerra Civil / the Spanish civil war >

- History of Xàbia (English articles) >

- Charlas y excursiones / talks and excursions >

- Investigacions del museu - Museum investigations

- Enllaços

- Enlaces

- Links

-

Historía de Xàbia

>

- Social media

- Visitas virtuales

- Tenda Tienda Shop

RSS Feed

RSS Feed